Pure Handel

November 10, 2020

Joy and Sorrow Unmasked (DVD)

November 10, 2020Vivaldi per Pisendel

€13.85

SUONATA Á SOLO FACTO

PER MONSIEUR PISENDEL DEL VIVALDI

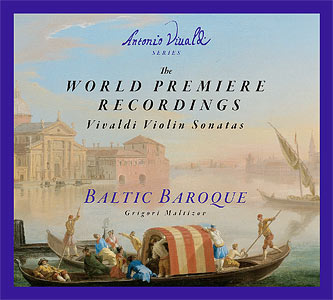

Antonio Vivaldi Series

Baltic Baroque, kunstiline juht Grigori Maltizov

CD

2012

ERP 6312

In stock

SUONATA Á SOLO FACTO

PER MONSIEUR PISENDEL DEL VIVALDI

Vivaldi Series

by BALTIC BAROQUE

First record of the Vivaldi Series. The World Premiere Recording of the 4th movement of Violin Sonata in G major, RV 25!

Diese Einspielung durch Baltic Baroque macht deutlich, dass diese Werke noch heute durchaus eine Herausforderung für professionelle Geiger sind. (Ouverture, 2013)

| 1-7 | Suonata á Solo facto per Monsieur Pisendel del Vivaldi in G major, RV 25 | 10:22 |

| 8-11 | Suonata á Solo facto per Monsieur Pisendel del Vivaldi in C minor, RV 6 | 12:05 |

| 12-16 | Suonata á Solo facto per Monsieur Pisendel del Vivaldi in F major, RV 19 | 17:38 |

| 17-21 | Suonata á Solo facto per Monsieur Pisendel del Vivaldi in C major, RV 2 | 15:57 |

| 22-25 | Suonata á Solo facto per Monsieur Pisendel del Vivaldi in A major, RV 29 | 6:52 |

![]() #10, Sonata in C minor, Mov IV, fragm, 3 min, mp3, 160 Kbps

#10, Sonata in C minor, Mov IV, fragm, 3 min, mp3, 160 Kbps

![]() #5, Sonata in G major, Mov V, 1 min 6 sec, mp3, 160 Kbps

#5, Sonata in G major, Mov V, 1 min 6 sec, mp3, 160 Kbps

![]() #23, Sonata in A major, Mov II, fragm, 1 min 34 sec, mp3, 160 Kbps

#23, Sonata in A major, Mov II, fragm, 1 min 34 sec, mp3, 160 Kbps

Ensemble Baltic Baroque

Ensemble Baltic Baroque

Grigori Maltizov – artistic director, producer

Maria Krestinskaya – baroque violin (#1−7)

Nazar Kozhukhar – baroque violin (#8−11)

Andrei Reshetin – baroque violin (#12−21)

Evgeny Sviridov – baroque violin (#22−25)

Sofia Maltizova – baroque cello

Imbi Tarum – harpsichord

Recorded in 2011 in Swedish St Michael’s Church, Tallinn (#8−11, 17−21), and in 2012 in St Jacob’s Church, Viimsi, Estonia (#1−7, 12−16, 22−25)

Engineered by Tanel Klesment (#1−7, 12−25) and Margo Kõlar (#8−11)

Liner notes by Anna Bulycheva

Booklet translated and edited by Tiina Jokinen, Inna Kivi

Front cover painting by Canaletto

Designed by Mart Kivisild

Executive producer – Peeter Vähi

On period instruments: baroque violin by Giovanni Paolo Maggini, 1627, Italy (#1−7); baroque violin by Johann Gottfried Hamm 18th cent, Germany (#8−11); baroque violin by Marcin Groblicz 17th cent, Poland (#12−21); baroque violin by anonymous, 18th cent, Italy (#22−25); baroque cello after Antonio Stradivari 1712, Italy; 2-manual French harpsichord by Samuli Siponmaa after Blanchet

Total time 62:52

Stereo, DDD

Liner notes in Estonian, English and Russian languages

Released in Nov 2012

ERP 6312

The CD bearing an original title by Antonio Vivaldi (1678−1741) presents sonatas dedicated by the latter to German violinist and composer Johann Georg Pisendel. The manuscripts of the works come from the library of the Dresden Court Orchestra to which Pisandel himself made regular contributions in the course of 30 years. Some of those 5 sonatas have found their way to the so-called Manchester collection. Considering the fact that Vivaldi’s violin sonatas Op 2 and Op 5 were already during his life-time published not only in his homeland but also in Amsterdam, we can get a fairly good idea of his popularity in Europe.

Johann Georg Pisendel (1678−1755) travelled around quite a bit in his youth until he settled down in Dresden, in 1712, becoming a violinist at the Court Orchestra. From 1728 until his death, he occupied the post of concert master excelling with his deep knowledge of the minutest details of the music to be performed. The job of court musician in Saxony, however, did not prevent Pisendel from travelling. Beginning with April 1716, he spent 9 months in Venice where he was rumoured to have studied with Vivaldi. Although it could hardly have been studies in the strict sense of the word, as by that time Pisendel, only 9 years younger than Vivaldi, was already one of the leading violinists in Germany, a respected and outstanding musician. It is more likely that Pisendel’s aim was to familiarize himself with the newer performing and composition styles in Italy. Soon after his return, Dresden became the foreground of Italian music and the new capital of opera in Germany. Vivaldi’s works found a firm place in the Court Orchestra’s repertoire.

During the days of young Vivaldi, two main forms of sonata were known: da chiesa (church sonata) and da camera (chamber sonata). Da camera is a dance suite connected by one tonality. In Early Baroque this was purely “applied” music. Da chiesa was, indeed, performed in churches. It did not contain dance rhythms and in one of the central movements, as a rule, the tonality had to change.

During the days of young Vivaldi, two main forms of sonata were known: da chiesa (church sonata) and da camera (chamber sonata). Da camera is a dance suite connected by one tonality. In Early Baroque this was purely “applied” music. Da chiesa was, indeed, performed in churches. It did not contain dance rhythms and in one of the central movements, as a rule, the tonality had to change.

In Vivaldi’s work the characteristics of da chiesa and da camera intermingle, forming unique moody combinations. Shedding the function of applied music and exiting the restricting premises of church and ballroom, sonata gradually acquired the form of “pure music”, where composer’s fantasy was given free will. The violin sonatas Op 2 and 5, published during Vivaldi’s life time, had 3 to 4 movements. The sonatas dedicated to Pisendel are even more extensive containing 4 to 7 movements.

Vivaldi’s sonatas grew like living organisms. Sonata RV 2 is a real “transformer”. Its 2nd and 3rd movements − a fanciful minuet of various articulations and a motive gigue − are utterly similar to the corresponding movements of RV 4, whereas odd-numbered movements of those “twin” works, however, are totally different. The 1st movement of the sonata on the present CD, is slow, while the 3rd is an extravagant siciliana with pathetic Neapolitan harmony. Pisendel, after getting this sonata, added to it an unusual fast sarabande as the 5th movement. Taking into account how little of the work by that German maestro has been preserved, every smallest bit is invaluable.

In Sonata RV 6 the patterns of da chiesa and da camera make an ideal merger. An especially strict prelude is followed by a brisk Italian courante, the 3rd movement being Grave in the meaning of “solemnly”, while the finale in Allegro is an allemande. That is a so-called “light” allemande − a short and passing fashion outbreak leaving an imprint in the form of a few pieces in the musical legacy by Couperin, Rameau and Bach. All those pieces are capriccio-like fast and moody, Vivaldi’s allemande here being no exception.

Among sonatas dedicated to Pisendel RV 19 has become a cult of motility: all the fast movements flow in uninterrupted succession. The 5th movement − finale in the form of variations − impersonates an encyclopedia of violin techniques, textures and rhythms.

As an only one of its kind Sonata RV 25 is a real dance suite. Its 7 (!) movements have all a pastoral tinge. The triply variating odd-numbered movements in major and even-numbered movements in minor create a unique effect of light and shadow. Vivaldi has not given names to the dances, nevertheless, they are easily recognized. The sonata begins with a peaceful siciliana followed by a light bourrée and minuet in popular style with suddenly emerging “wrong” beats that deliberately defy the rules. The 4th movement is another siciliana − the “twin” in minor of the 1st movement. The 5th movement (Gigue) is so brisk that for the first time on the current CD, cello starts competing with the violin. All that is followed by a “light” allemande, finished up by a new minuet with bold syncopes and brilliant repetitions. The latter is composed on a laconic theme allowing a multitude of repetitions making it sound like a merry poem with short verses. Those were a frequent phenomenon in pastoral works and Vivaldi, himself occasionally writing a verse or two, knew poetry well.

Sonata RV 29, contrary to the former, is “pure” sonata without a single dance. The two first movements contain a multitude of double, triple and even quadruple notes. From the third movement the texture gets lighter while the violin part is no less complicated. It can generally be felt that Vivaldi has composed his Sonatas dedicated to Pisendel for a real virtuoso whose instrumental skills were to be admired. The composer’s attention is solely centered on the violin part. In many pieces the technical virtuosity grows through the work. Occasionally, the violin is given two voices. In the Grave of RV 6 the violin seems to be talking in two voices: the upper voice is a reciter and the lower one, at first not so talkative, gets carried away by the upper. This part is full of expressive passages – a superb example of musical rhetorics. At times, it can be felt that Vivaldi has not given up the trio sonata tradition of two upper voices and bass. That is exactly was his Twelve sonatas Op 1 is. While in transition to more fashionable and perspective solo sonatas, time and again, he would turn back to the texture of trio sonatas. In the minuet of Sonata RV 2 the second violin grabs single notes even from the part of basso continuo. The violin part is nearly self-perfect, just a little more and the accompaniment becomes unnecessary. This is precisely the experiment that Johann Georg Pisendel tries to conduct in his Venice-born Solo sonata in A minor for violin.

In the current sonatas by Vivaldi the huge inequality of ensemble parts is especially conspiquous. The bass part carries a function of simple accompaniment. At a couple of times the bass catches single notes from the violin part but this never develops into an equal dialogue.

In other sonatas by Vilvaldi the continuo part is handled and interpreted totally differently. In the Pisendel sonatas, the composer has written down only the melody line of the bass without marking chord numbers (the numbers could be found sporadically only in Sonata RV 6 that has been notated by the composer’s father Giovanni Battista Vivaldi). This indicates Vivaldi’s total trust in the professionalism of his German colleagues who did not need him prompting the harmony. Ovbiously, Maestro was also too busy in order to polish his manuscripts the way he worked with the material for publishing and printing. His hasty, though expressive handwriting allows us to draw conclusions about the speed of composing the sonatas as well as to take a glimpse at the fantasy and temperament of the author.